MassTransit is capable of a lot, and one important feature is Send vs Publish. If you read the official documentation section “creating a contract“, it talks about commands (send) and events (publish). This makes sense, because commands you want to only be executed once, however events can be observed by one or more listeners.

This tutorial will look at what is happening with the two different message types. To follow along, download the completed project here. The only thing you will need to do is create a virtual host and user in RabbitMQ. Other tutorials for MassTransit typically use the default RabbitMQ guest/guest account, but I prefer to separate mine into virtual hosts. So open the solution and look in either of the three services App.config or the Mvc Web.config. You’ll see:

<add key="RabbitMQHost" value="rabbitmq://localhost/tutorial-send-vs-publish" /> <add key="RabbitMQHostUsername" value="tutorial-send-vs-publish" /> <add key="RabbitMQHostPassword" value="chooseapassword" />

So browse to http://localhost:15672, login as admin and configure. I make the virtual host and username the same. Then choose a password you want. After it’s setup run the solution and try it out!

Tutorial

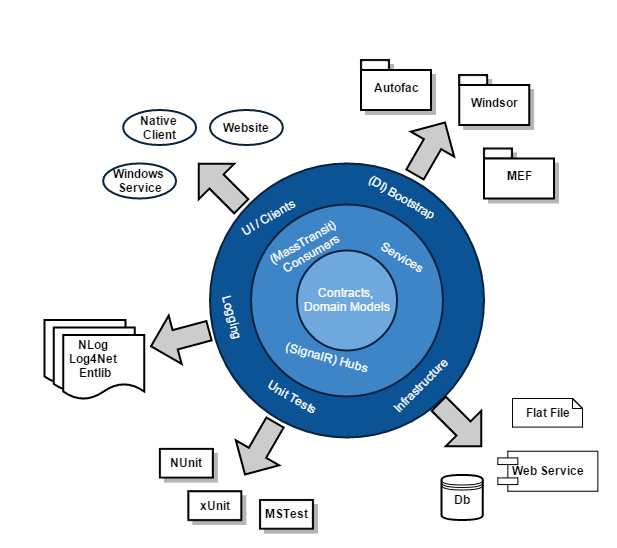

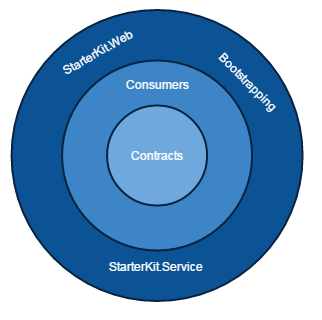

I started with the Mvc StarterKit and created 3 services. One service is for the events (in practice it could be 1..n). The other two services for commands have artificially fast and slow processing speeds. This was done to illustrate that although X quantity of commands are queued, they are only processed once (well, once or more to be honest, as RabbitMQ is a ‘at least once’ message broker).

Note #1: Commands and events are both usually defined as interfaces. Therefore using descriptive names helps discern commands from events.

Publish (Events)

Lets use a post office and mailbox to help describe publish. An event in MassTransit is akin to flyer’s that we receive in the mail. They aren’t directly addressed to us, but everybody who has a mailbox gets them. So flyer = event, and mailbox = endpoint. When building your bus and registering an endpoint like so: sbc.ReceiveEndpoint(…), one has to be sure that the queueName parameter is unique. This is emphasized in the “common gotcha’s” part of the documentation. Now although it’s called queueName, it actually makes an Exchange and Queue pair, both named after the queueName parameter.

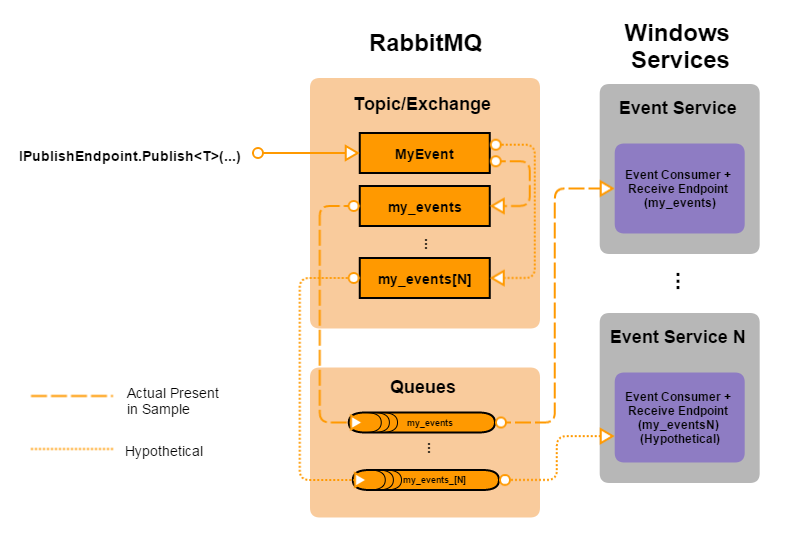

The below diagram shows the MyEvent flow in the sample project.

Although the sample doesn’t have multiple event services, I added my_events[N] just to show you each new service (and receive endpoint) will have a corresponding exchange+queue pair made.

Note #2: Now when I’ve used MassTransit and RabbitMQ, I’ve never worked with high traffic projects that result with queue or service bottlenecks. I believe RabbitMQ can be thrown quite a lot and keep up, but if you are encountering thresholds for RabbitMQ or the service, then you will need to think about RabbitMQ clustering, or adding more services (perhaps even scaling out services). But these are highly specialized and more advanced topics. My advice would be to use the MassTransit and RabbitMQ community discussion boards or mailing lists.

Send (Commands)

Commands should only be executed once (although you should be aware if making commands idempotent, but we will not cover this more complex topic in this tutorial). So in our scenario above (publish), if we have multiple services (ie. multiple endpoints) for the same contract type, we will have a single command being executed by many consumers. So rather than publish, we send a command to a specific queue+exchange pair. Then, our services can connect to the same receive endpoint’s queueName so long as they have the same consumers registered. I’m paraphrasing this important point from the documentation.

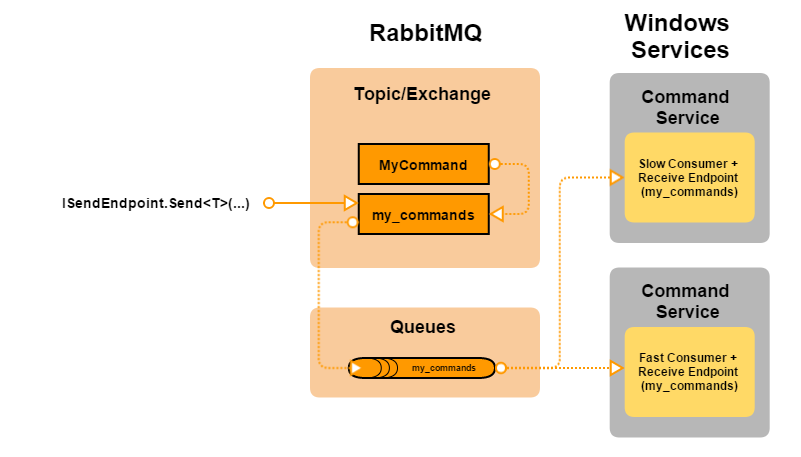

Here’s the MyCommand flow in the sample project.

The one main difference is the Message is sent directly to the my_commands endpoint exchange, rather than the MyCommand contract exchange. This avoids the contract exchange fan-out. In the sample, we also chose our services to subscribe to the same endpoint (as I made sure they both had the same consumers registered). I cheated a little and added a different sleep time to each consumer.

Code Comparison

To publish:

await _bus.Publish<MyEvent>(...);

Pretty simple, nothing to explain here

To send:

var sendEndpoint = await _bus.GetSendEndpoint(new Uri(ConfigurationManager.AppSettings["MyCommandQueueFullUri"])); await sendEndpoint.Send<MyCommand>(...);

The big difference, we have to get our send endpoint first by passing in the Full Uri.

I hope this has helped clarify commands vs events, and when to use each. The next post I have planned will look at Transient vs Persistent exchanges+queues.